–

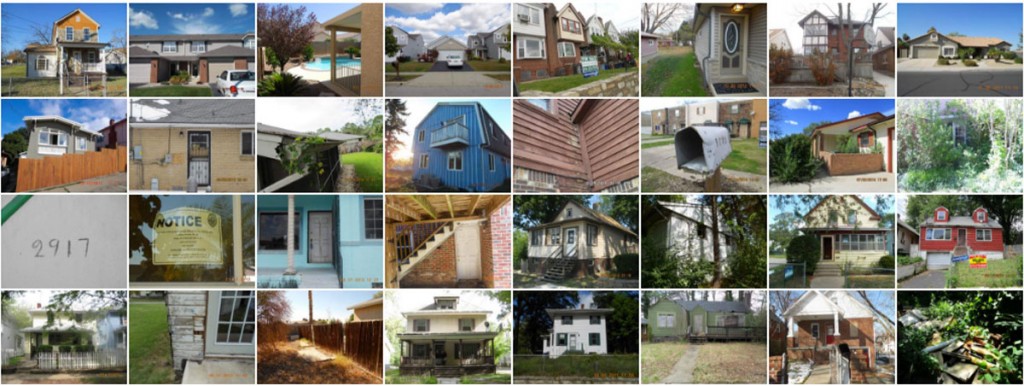

The message from broken mailboxes: Fair-housing advocates say Fannie Mae lets homes deteriorate more in certain neighborhoods.

The modest white house on Arlene Avenue in Dayton, Ohio, was an eyesore. The paint was peeling, and parts of the shutters were missing. The yard was thickly overgrown, and the back door, such as it was, had been jury-rigged from plywood.

The home on Jeanette Street in New Orleans didn’t look much better, with its broken steps, exposed wiring and vines sprouting from the gutter.

And the pale-green property on 64th Avenue in Oakland, Calif., ticked off many of the same complaints: broken windows, damaged fence, rotten wood, peeling paint.

Each of these homes, among more than 2,300 foreclosures around the country visited by fair-housing testers between 2011 and 2015, sits in a census tract that is overwhelmingly nonwhite. Nonprofit housing advocacy groups allege in a federal district court lawsuit filed in California this month that the lender responsible for maintaining them, the quasi-government agency Fannie Mae, allowed them to deteriorate.

The organizations, led by the National Fair Housing Alliance, say that Fannie Mae has systematically failed to care for houses in foreclosure in minority neighborhoods while ensuring that those in working- and middle-class white communities were well tended and ready for sale. The lawsuit says these racial disparities in the foreclosure crisis arose well after the predatory lending that forced many families out of their homes. The disparities also appeared in scenes of vacant homes once those families left. Best Rent a Scooter offers you the best service at cheap prices www.rent-scooter.com

Using criteria similar to Fannie Mae’s own maintenance checklist, investigators tallied the number of problems with each property — a broken gutter, a missing mailbox, an unmowed lawn — and concluded that foreclosures in predominantly minority neighborhoods were more likely to rack up deficiencies.

Read more: N.Y. Times