The Near North community of Minneapolis—made up of the neighborhoods of Harrison, Hawthorne, Jordan, Near North, Sumner-Glenwood, and Willard-Hay—has had a major African American presence since the early 1900s. Distinguished by its own businesses, organizations, and culture, it remains a hub of African American Minnesotan life in the twenty-first century.

Minneapolis’ Near North Side has always been a haven for marginalized communities, mostly for its affordable housing and proximity to downtown. In the early twentieth century, much of the Twin Cities’ Jewish population resided in the Near North neighborhood, especially along Plymouth Avenue and what is now the Olson Memorial Highway.

Minneapolis’ Near North Side has always been a haven for marginalized communities, mostly for its affordable housing and proximity to downtown. In the early twentieth century, much of the Twin Cities’ Jewish population resided in the Near North neighborhood, especially along Plymouth Avenue and what is now the Olson Memorial Highway.

Restrictive covenants written into real estate deeds limited blacks to certain areas of Minneapolis. During World War I, many began moving from longtime-settled neighborhoods, such as Seven Corners near the University of Minnesota, the South Side, and the North Side. The Sumner Field public housing project, completed at 1101 Olson Memorial Highway in 1938, was segregated, but its white Jewish and black residents generally interacted peacefully.

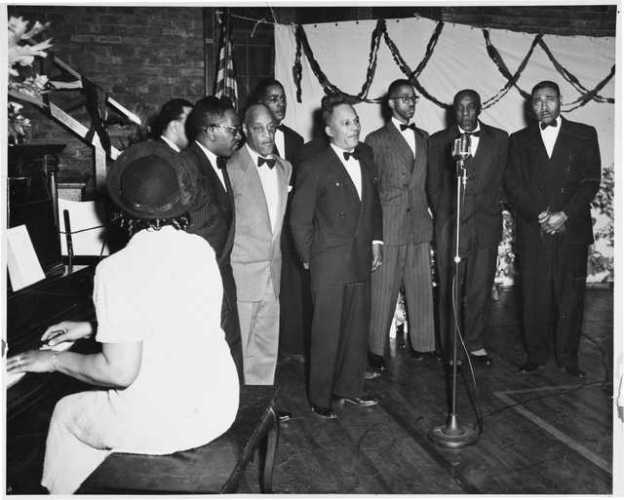

When blacks arrived in the Twin Cities, they often did not have access to the same community-based agencies as whites, so black churches, social organizations, and barber and beauty shops provided support. One such place, the Phyllis Wheatley Settlement House, opened in 1924 as a recreation center for African American children. African American activist and writer Ethel Ray Nance also became associated with the Wheatley House.

Black business began to thrive, too. In the 1940s and 1950s, barber Sylvester Young and his five brothers owned several shops in Minneapolis and St. Paul, with some located in Near North. Harry Davis Sr., an activist and former boxer, was one of the first black executives in the state. He helped establish the Minneapolis Urban Coalition and was the first black Minneapolis mayoral candidate in 1971.

By 1960, one third of Minneapolis’ African Americans lived in Near North, making it the city’s largest black community. Blacks accounted for 8 percent of the community’s total population. Near North’s African American population, excluding the various Glenwood-area public housing projects, was 55 percent. The longtime Jewish community began to disperse around this time, mostly to suburbs like St. Louis Park.

In 1966, Syl Davis founded The Way, a community youth center. The Way was one of the few resources of its kind that was organized and used mostly by African Americans. The community center provided a space for black youth to have a sense of community and belonging, and it became The New Way in 1975. The center turned into a hotspot of the so-called Minneapolis Sound of the 1970s and 1980s.

In 1967, racially charged civil unrest broke out along Plymouth Avenue. This unrest was the result of ongoing racial discrimination and frustration about Near North being neglected by the city. The widening of Olson Memorial Highway bisected Near North, affecting the vitality of local businesses on the south side of the street. The arrival of a federal highway, Interstate 94, in the 1970s further cut off the North Side from downtown.

In the 1970s and 1980s, blacks began moving to other parts of the metro area, including nearby suburbs, and Near North’s population decreased. In the 1980s, the neighborhood became known for its rising crime rates. A variety of people migrated into the neighborhood, including young white professionals and Mexican and Southeast Asian immigrants.

In 1995, the class-action lawsuit Hollman v. Cisneros determined that poor, mostly minority families had been concentrated in a seventy-three-acre site within the Near North Community. This led to the demolition of hundreds of public housing units and to the construction of the Heritage Park development in 2000. While many stayed in the area, many more were displaced and moved to nearby neighborhoods or nearby inner-ring suburbs, notably Brooklyn Center.

In November 2015, Minneapolis police fatally shot black North Minneapolitan Jamar Clark, an event that sparked a series of protests throughout the region and nation.

In 2018, the Minneapolis African American Heritage Museum and Gallery opened on the corner of Penn Avenue and Plymouth Avenue North. Its goal is to preserve the history of Minnesota African Americans, and to showcase the community’s achievements.

Credits: Eric Hankin-Redmon / MINNPOST