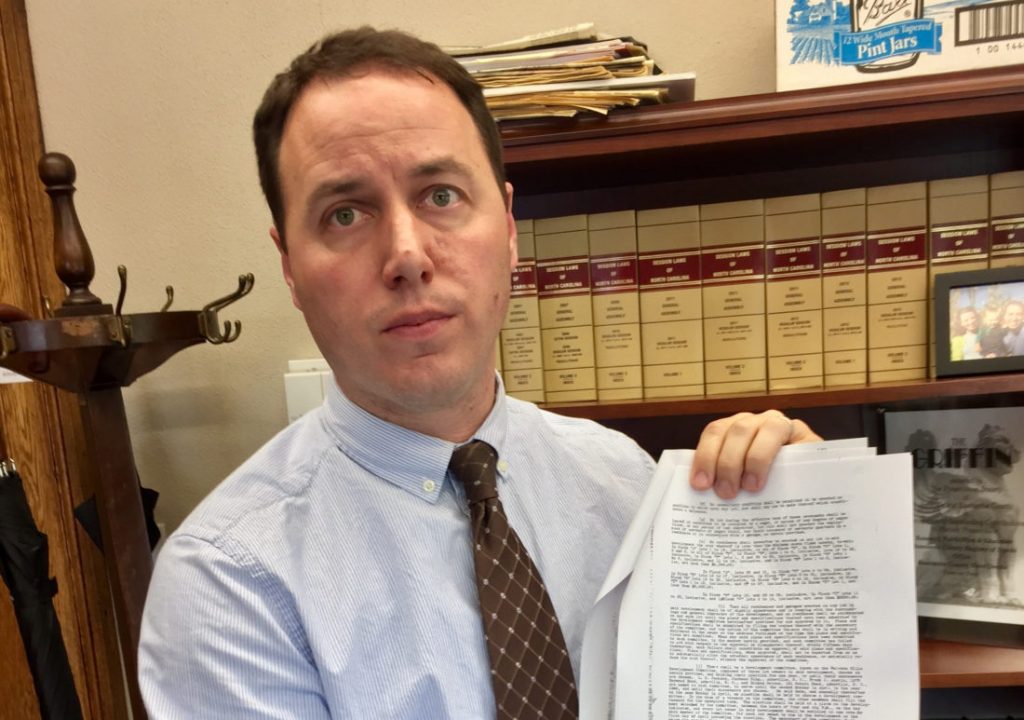

It’s rare that Drew Reisinger, Buncombe County’s register of deeds, is surprised by any historical outrages that turn up in the public records under his care. After all, it was at his direction that the county became the first one in the country to digitize its archives of deeds documenting the local ownership and sale of slaves.

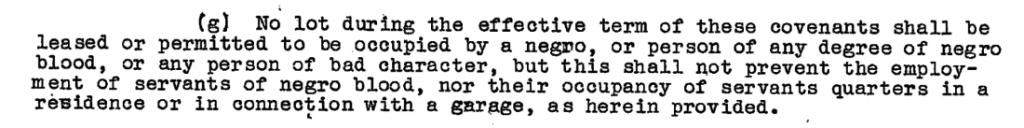

But one day in 2013, as he reviewed a title search for the home he and his wife would ultimately buy — a medium-sized rancher on Wendover Road in West Asheville’s Malvern Hills neighborhood — one of the restrictive covenants listed in the property records left him cold. Scripted in 1939 by a now-defunct homeowners association, it read: “No lot … shall be leased or permitted to be occupied by a negro, or person of any degree of negro blood, or any person of bad character.” The covenant went on to clarify that “This shall not prevent the employment of servants of negro blood, nor their occupancy of servants quarters.”

“I was shocked and saddened,” Reisinger remembers. “I can only imagine what it would have been like to find that kind of message if you were a black person thinking about joining this neighborhood, how unwelcoming and even scary that would be.”

Tucked into real estate deeds and other lengthy legal documents regulating property use and maintenance, aesthetic standards and the like, such racial restrictions were once prevalent in states throughout the nation. According to The Fair Housing Center of Greater Boston, “Most covenants ‘run with the land’ and are legally enforceable on future buyers of the property.” Owners who violated the terms of the covenant risked forfeiting their property or, in some cases, incurring significant fines.

And though both the courts and federal housing law long ago ruled such covenants unenforceable, they remain on the books in many communities to this day. In the Malvern Hills case, a quorum of neighborhood property owners rescinded the ban on black residents in 1963 as the civil rights movement was gaining steam.

A search of old Asheville property deeds turns up many such vestiges of institutionalized racism. One that was rescinded by the Biltmore Forest Co. in 1970, for example, used almost the exact same language, banning any “negro or person of any degree of negro blood.” Likewise, a covenant in East Asheville’s Beverly Hills neighborhood, not revoked until 1983, stressed that “No persons of any race other than the Caucasian race shall use or occupy any building.”

And in North Asheville’s Lake View Park development, even a 1940s welcome pamphlet for property owners touted a ban on black residents, alongside details about such amenities as Beaver Lake and its boating, fishing and swimming opportunities. The development’s current website contains assorted historical documents including the pamphlet, with a note indicating that it was produced in the “pre-civil rights period.”

No one knows how many Asheville neighborhoods or properties were once subject to racial covenants, and to find out would require exhaustive research in Buncombe County’s land records.

“These things are buried all over the place,” says Reisinger. And while he’s glad to find that many neighborhoods did eventually officially renounce those restrictions, he adds, “This is a history we obviously haven’t taken a very close look at, and that’s something we need to do.”

Even before many of the local covenants were written into property deeds, Asheville was an early adopter of racial housing restrictions. In 1913, for example, the city enacted a segregation ordinance creating separate black and white residential zones. But subsequent Supreme Court cases shed light on the way both racism and legal efforts to combat it can evolve over time.

Buchanan v. Warley, a 1917 decision concerning a similar law in Louisville, Ky., declared such municipal racial zoning unconstitutional. That didn’t eliminate the underlying prejudice, however: It simply morphed into a different form.

In Asheville, for example, assorted prominent citizens endorsed a sweeping new blueprint for the city’s future in 1922. Prepared by John Nolen, a noted urban planner who also designed Lake View Park, the Asheville City Plan stated, “It is in most respects a distinct advantage to the negroes to be separated from the white population” — provided that black residents had good schools, homes, stores and recreational areas.

Reflecting such sentiments, many of the Asheville subdivisions built during the 1920s boom barred black ownership, notes local real estate attorney William Reed. “At the time, it was a clear reflection of some of those white communities’ racial beliefs and preferences,” he says. “They were unabashed about the fact that they didn’t want people of color as their neighbors.”

Accordingly, private racial restrictions — i.e., those not issued by a unit of government — proliferated nationwide. North Carolina was one of 14 states whose supreme courts upheld the legality of racial covenants when they were challenged, according to historian Richard Rothstein’s 2017 book The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. And in 1926, the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Corrigan v. Buckley upheld those restrictions’ validity. Rothstein is an authority on institutionalized discrimination.

By 1948, however, the court’s position had shifted. That year, the landmark Shelley v. Kraemer ruling dealt racial covenants a theoretical deathblow, declaring them unconstitutional and unenforceable. But as Rothstein notes, the Federal Housing Administration “continued to subsidize projects that penalized sellers of homes to African Americans,” and new racially restrictive provisions still crept into legal documents pertaining to some residential associations and housing developments, even decades later.

In Asheville, other types of housing discrimination appeared after restrictive covenants lost the force of law. Some of those practices, particularly “redlining,” continued on a large scale for decades, notes local racial equity consultant Marsha Davis. She’ll recount the city’s history of redlining — the refusal by banks and insurance companies to issue loans or policies in certain neighborhoods — at a Thursday, May 30, event hosted by financial counseling nonprofit OnTrack WNC (see sidebar). Her presentation will outline various steps taken to disenfranchise, displace and corral black communities.

Today, many homeowners may not even be aware that their property was once subject to racial restrictions — and if and when they do find out, they can be flummoxed about how best to respond. In recent years, a few states, including California and Washington, have passed laws allowing individual owners to expunge discriminatory language from their deeds, but North Carolina has no such provision.

Upcoming talk explores institutionalized racism WHAT “Redlining in Asheville: Racism Disguised as Housing Policy,” presented by Marsha Davis of Davis Squared Consulting WHERE OnTrack WNC 50 S. French Broad Ave. 828-255-5166 ontrackwnc.org WHEN Thursday, May 30, 10-11:15 a.m., followed by the nonprofit’s annual Financial Literacy Awards Luncheon, 11:30 a.m.-1 p.m. Admission is $10 for talk, $35 for luncheon, $40 for both

“Even when these covenants are still on record, of course, they can no longer can be invoked or enforced,” notes Reed, the real estate attorney. But that doesn’t stop some present-day owners from seeking to erase what they consider a stain on their property’s history.

Reed cites a 2009 case in which he assisted a black couple buying a house in Lake Toxaway in Transylvania County. The couple were chagrined to learn that the 1961 property deed banned “any person or persons not of the Caucasian race” (with an exception for “servants”). With Reed’s help, after buying the home, they filed a “termination of restrictive covenant” document — an addendum to the deed that, at least symbolically, renounced the racial restriction.

The document noted that both federal and state law have long banned discriminatory housing practices and spelled out the couple’s rejection of the covenant.

“You might say there’s no need for such a declaration,” Reed points out, since the restriction was already legally invalid. “But they decided that it was a concrete way to say that the values of the old owners are no longer welcome, that we have new values now.”

Whether or not old racial covenants are disavowed, they still tell an important story, argues Durham resident Stella Adams, the North Carolina NAACP’s housing chair and a veteran fair-housing advocate. During the 2000s, she studied cities where the covenants had been widely used, including Asheville, Charlotte and Wilmington.

And despite racial covenants’ lack of legal standing, Adams says their impact remains evident, even now. “In so many of these communities, you can examine the racial makeup of when the communities were built, and it’s exactly the same today,” she says.

Davis, meanwhile, believes that an examination of practices like racial covenants and redlining must inform contemporary strategies for countering deep-rooted inequalities wherever they are found.

“When we look at the achievement gap, the wealth gap, health gaps — all these stark disparities between races — it’s impossible to discuss them without taking a clear look back,” she maintains. “You can’t solve a problem without knowing where it came from in the first place.”