By Jacob Passy

A new report outlines how little has changed since 1968 when it comes to housing and minorities

For many minority households across the country, the rent really is too damn high.

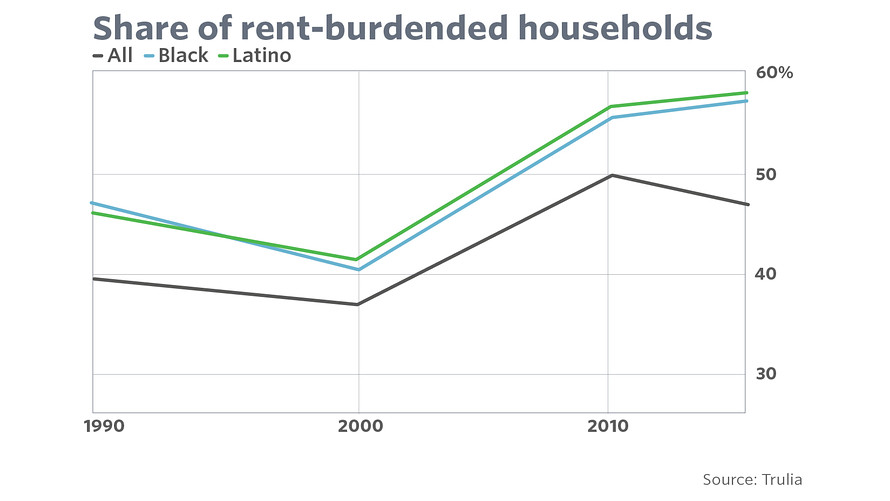

The share of rent-burdened black and Latino households exceeds 55% in the 100 largest U.S. cities compared to 47% of the overall population, according to a report from real-estate website Trulia that looks at the state of housing nearly 50 years after the passing of the Fair Housing Act of 1968. Rent-burdened in this case means those households spend more than 30% of their income on rent. And while the share of rent-burdened households nationwide has fallen since 2010, it’s gone up in black and Latino communities.

Regionally, the impediment imposed by rental payments is even more pronounced. In Grand Rapids, Mich., for instance, more than 69% of black renters are rent-burdened. That’s also the case for nearly 67% of Latino renters living in Miami.

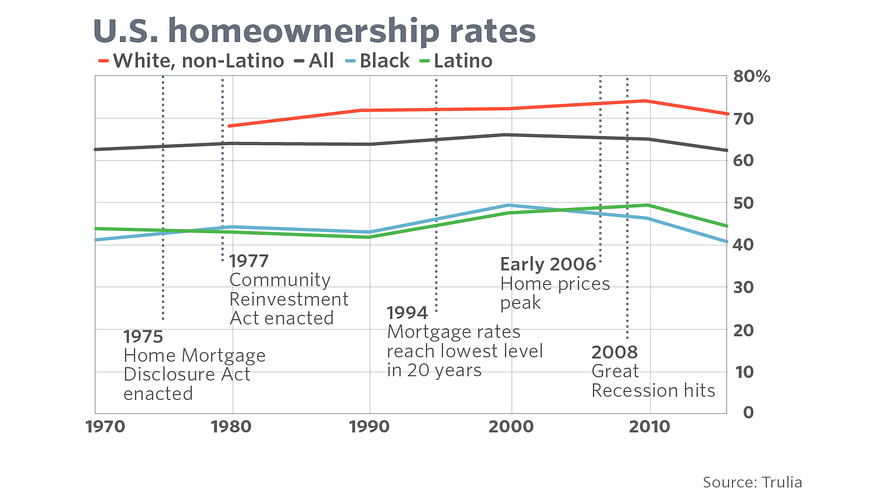

Compounding this issue, homeownership rates among minority households have remained more or less unchanged over the last 50 years. The black homeownership rate, however, actually experienced a decline from 2000 to 2010 and fell behind the homeownership rate among Latino households during that time. “The Great Recession disproportionately impacted black and Latino households as gains in these housing opportunities before 2000 were largely erased in the last 10 years,” Cheryl Young, a senior economist at Trulia, wrote.

Since 1980 the gap between white homeownership rates and black homeownership rates actually widened to 30.6% from 24.1%. And because homeownership is one of the biggest generators of wealth, black and Latino communities have not seen the same growth in net worth as their white counterparts.

The relatively high burden created by rent is one of the many reasons there continues to be a major gap in the homeownership rates between white and minority households. But it’s far from the only issue, said Maurice Jourdain-Earl, managing director at ComplianceTech, a consulting firm and software vendor that specializes in legal and regulatory issues in consumer lending.

“Access to credit is a major, major issue,” Jourdain-Earl said. “Lenders have not been making loans proportionately to people of color.”

That problem is in part a structural one, Jourdain-Earl said, related to how loans are underwritten. As a result, black and Latino homebuyers who do receive a mortgage are more likely to be offered a loan insured by the Federal Housing Administration, even in instances where they could qualify for loans not intended for low-income borrowers. And because FHA loans come with the added expense of mortgage insurance, which is required for the life of the loan, these products can be costlier than other options.

Another issue: affordability. While higher home prices have affected most people across the U.S., the gentrification of urban neighborhoods has had an outsized effect on minority communities. “Neighborhood improvement is largely not to the benefit of people in those neighborhoods,” Jourdain-Earl said, noting that many people of color are being “pushed out beyond the suburbs.”

Still, in one major way housing has improved: Segregation has declined. In all but six of the top 100 metropolitan areas nationwide residential segregation between white and black communities went down. And three of those six cities — Rockville, Md., Peabody, Mass., and Honolulu — experienced some of the largest increases in black homeownership, which Trulia suggested could indicate that upper-income African-Americans have formed their own enclaves in these areas.

On the other hand, more increases in Latino-white segregation were noted, which Jourdan-Earl suggested is potentially indicative of recent immigration trends. In recent decades, cities of the Midwest and South have seen an influx of Hispanic immigrants, with many of these families clustering within the specific neighborhoods in these areas. “That’s happening a lot because of the underlying anti-immigrant sentiment, whereas black people in those areas have been there for hundreds of years,” he said.

Segregation was extremely pronounced in cities such as cities in Florida and Texas when the Fair Housing Act was passed, so even a small improvement in some of those areas will be noteworthy. “The segregation is still there,” Jourdain-Earl said. “You can see where the lines of demarcation are. You can see where bank branches may be located versus a payday lender or check casher.”